Angela Jones

Making Waves Across New England - Angela Jones

Angela Jones, a local diver, marine biologist and an award-winning photographer who has many distinguished milestones examining sea star characteristics. She is currently finishing her PHD at Northeastern University (NEU) in Boston and dives year-round in New England, Panama, and Curacao. Angela plans to continue mentoring the next generation of scientists through outreach at the Northeastern Marine Science Center, Museum of Science Boston, and eventually as a professor in marine biology.

During Angela's time in Panama, she works as a Teaching Assistant for the world-renowned Three Seas Graduate Program from NEU where Master’s students spend 6 months in Boston, 3 months in Panama, and 3 months in Washington state gaining valuable experience in several categories.

And while in Curacao, Angela assists in research as the Proteus Ocean Group science intern. Proteus Ocean Group is a distinguished program which aims to launch an underwater equivalent of the International Space Station - a collaborative global research platform to advance Ocean science.

Chris Solem introducing Angela as a Scientific Presenter for the 2024 Black History Month Celebration at Museum of Science, Boston. Photo credit Ashley McCabe and MOS.

Angela Jones knew from a very young age that she wanted to be a biologist. She began volunteering at Point Defiance Zoo and Aquarium in Washington State to gain experience working with larger animals. Unfortunately, while attending a mammology course in her undergraduate at Humboldt State University in California, she discovered she has severe allergies to dust and fur during her experience working with waterfowl birds, deer, foxes, and owls. She pivoted to the ocean for her studies and that's what brought her into the world of SCUBA diving in 2020! She has since been involved in sea star studies both locally and internationally.

During Angela's first research job in the rocky intertidal zone, a devastating Sea Star Wasting Disease (SSWD) outbreak began. This 2013 outbreak resulted in 5 BILLION sea stars dying on the West and East Coasts of North America. Since then, Angela has participated and led studies on sea star biodiversity, morphology, and ecology.

While completing her Master of Science in Biology in 2019, Angela examined the West Coast sea star Pisaster ochraceus (the Ochre Sea Star), famous for being a top predator of mussels in the intertidal and shallow subtidal. Her experience led her to join IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) Marine Star Specialist Group as an expert sea star biologist joining a team of international experts with a focus of increasing global sea star conservation efforts. This specialist group works on assessing populations of sea stars all over the world and connecting experts to help inform policies.

Angela Jones is halfway through her PhD at Northeastern University. There she works in the labs of Dr. Brian Helmuth and Dr. Mark Patterson- both Aquanauts meaning that they have lived underwater in saturation for many days at a time. In the lab, Angela examines common New England sea stars, Asterias forbesi (the Forbe’s Sea Star) and Asterias rubens (the Common Sea Star). Angela uses underwater photography, microscopy, and even CT scans of the sea stars to examine their characteristics. She aims to better understand how these top predators handle environmental stress with varying morphological characteristics that haven’t been studied since 1907.

Photo of Angela preparing her gear for another dive in Curacao in May 2024. Photo credit to Mark Patterson.

Angela has always been interested in sea stars as a whole, which has resulted in them becoming part of her personality over the many years of research. Through SCUBA, she is able to witness and photograph many more species than before.

Angela won several awards for her photography with best CT scan from the American Microscopical Society and 2nd place for 2023 Visuals of Marine Life and Conservation for the Underwater Society of America.

Learn more about Angela Jones:

www.angelajjones.com

helmuthlab.cos.northeastern.edu

Additional References

IUCN SSC Marine Star Specialist Group

Sea Star Wasting Disease

www.proteusoceangroup.com

Sea Stars Found in New England (by Angela Jones)

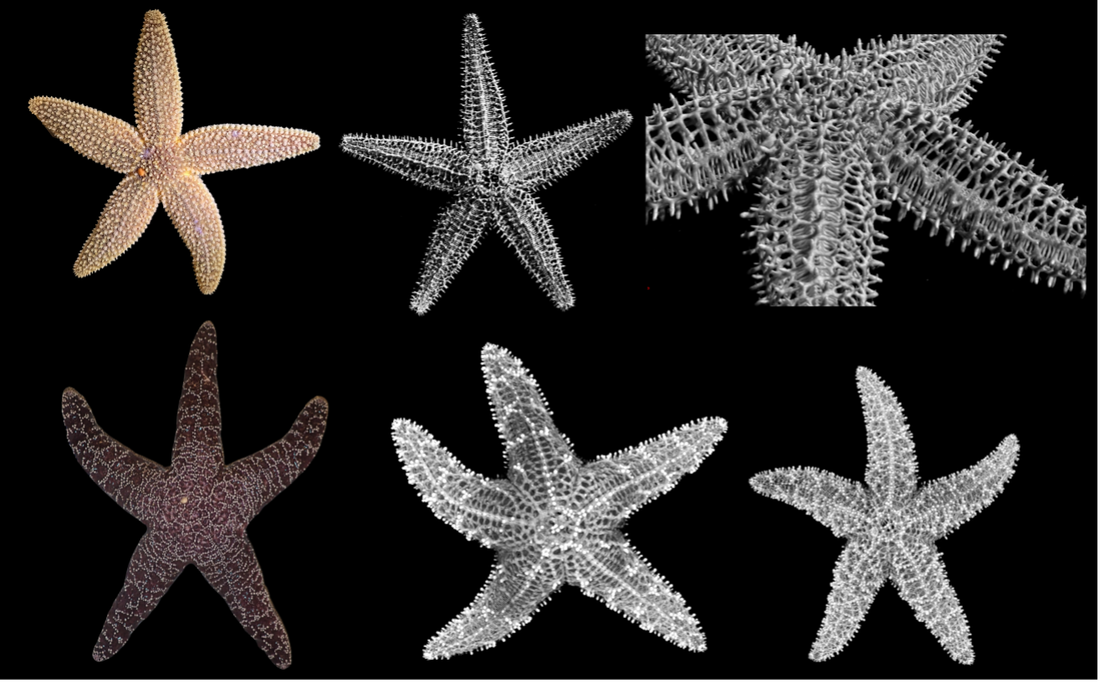

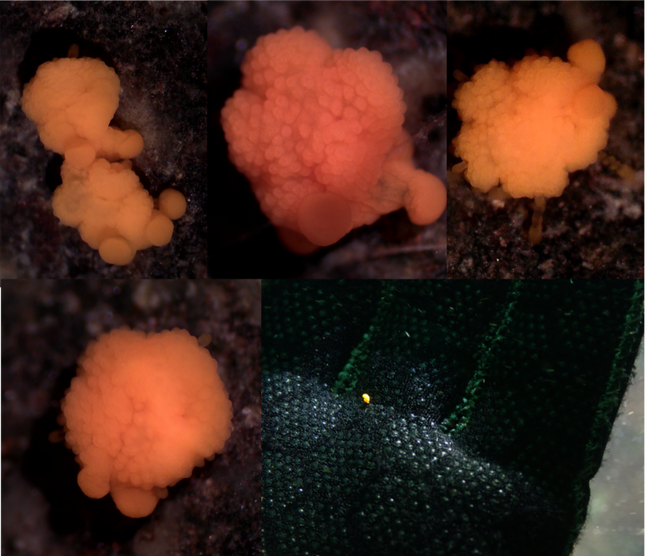

Sea stars from the genus Asterias

Sea stars from the genus Asterias as adults. They use their tube feet on the underside of their arms to move around and breathe. The tip of each arm has an ocelli (in red in the two far right photos) which is a very simple eye that can see simple shadows. The ocelli are surrounded by sensory tube feet that are thinner and longer than the locomotive tube feet and help with sensing prey.

The top row of stars are the Forbe’s sea star, Asterias forbesi.

With a life star on the left and a preserved sea star that has undergone a micro CT scan which took over 2600 images which allows researchers to reconstruct 3D models of the sea stars and even 3D print them.

The bottom row is Pisaster ochraceus, the Ochre sea star, that resides in the Pacific from Alaska to Baja.

The sea stars were scanned by the wonderful team at Micro Photonics.

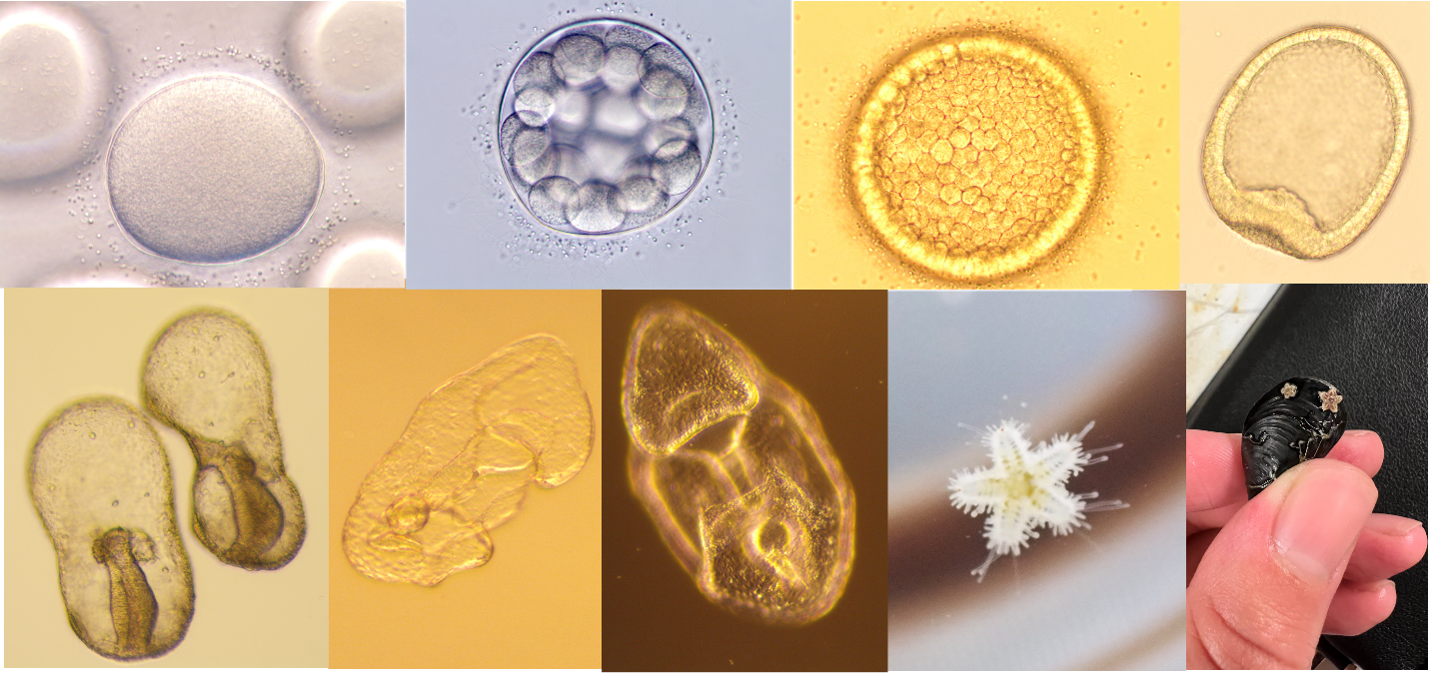

Asterias is a broadcast spawning organism which means that the sea stars release their gametes (egg or sperm depending on the individual) in the spring and early summer. Females can release up to 2.5 million eggs in one go. The embryos go through two metamorphoses before they become the recognizable sea star.

The larval stages can last between 60 days to over 100 days depending on food availability and environmental conditions. They are able to reduce their body size when food is low and regenerate at all life stages. Because of this, sea stars are very hard to age, but the estimate is about 10-15 years for Asterias.

The larval photos were taken from April 24th to May 31st when contamination took over this spontaneous project.

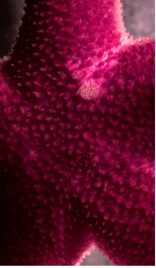

Sea stars from the genus Asterias

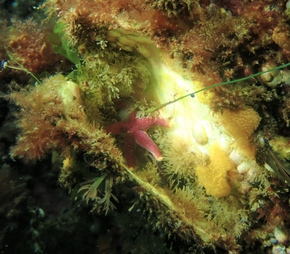

Sea stars in the genus Henricia are referred to as blood sea stars, but many people also refer to them as Henries for short. Henri adults are about an inch or two in size. Some of the species are brooders which means that they make small (but large egg size) broods which the mothers sit on and take care of until the stars are juveniles.

Henri juveniles from a brood in Gloucester, MA. Photos taken using a stereomicroscope at Northeastern University.

To stay attached to each other and their mother in the brood, the juveniles have 4 very large tube feet that help them stay attached as they develop.

As they age, they absorb or lose the larger tube feet in favor for smaller, more mobile ones (as seen in the top right photo).

Bottom picture is one of the juveniles on Angela's dive glove under water.